Culture

/

December 23, 2024

A speed demon at the typewriter, Malzberg wrote quickly and brilliantly in a variety of genres including mystery, thrillers, and erotica, but his core work was in science fiction.

If your life absolutely depended on it, could you write a readable and publishable novel in 27 hours? In early February of 1969, that was the task an editor at Midwood books foisted on Barry Malzberg, then a 29-year-old rising star in the seedy world of the paperback quickie. Midwood specialized in soft-core erotic fiction, often with a sapphic bent. Over the previous year, Malzberg had proven his chops by knocking off seven novels for Midwood, writing under the pen names M.L. Johnson and Mel Johnson titles like I, Lesbian and Nympho Nurse. The editor was in a jam: He had promised the publisher too many titles, one of which he was planning on writing himself, called Diary of a Parisian Chambermaid, but the deadline loomed terrifyingly close as he had to prepare for a vacation in Argentina.

The editor asked Malzberg if he could deliver the book in a few days. Malzberg, full of the impudence of youth, replied, “Try me.”

On February 13, Malzberg sat down at the typewriter at 8 am and started banging away at his top rate of 60 words a minute, which gave him between 3,000 to 4,000 words an hour. Malzberg paced himself, taking time off to eat, go for a few walks, and sleep. He finished the book the next day, appropriately enough Valentine’s Day, at 11 am. From start to finish, the novel took him 27 hours, with 16 of those feverishly pecking at the typewriter. The book was duly published under the pen name Claudine Dumas and Malzberg collected his fee of $1,500, giving him 2.5 cents a word for a 60,000-word opus. Malzberg worked, he said, “at an hourly wage rate that would astonish even a teamster.”

Malzberg, who died in a hospice in New Jersey on Thursday at the age of 85, flourished in the world of pulp fiction where quick writing was common: Malzberg’s friends Isaac Asimov and Robert Silverberg would both compile bibliographies of more than 500 titles. But even in that hurly-burly realm, Malzberg was a marvel. Reflecting on Diary of a Parisian Chambermaid in 2017, Malzberg told a podcast that, “in my opinion, with all deference to some writers we can name, it is the best novel written in 16 hours ever.” Malzberg did allow that Silverberg, if given a few days, could have written something superior. Although he never made great claims for such scutwork, Malzberg described Diary of a Parisian Chambermaid as “better than it has any right to be. It was readable.”

The key fact about Malzberg was not just that he was fast—but that he was good. Perfectly readable was his baseline minimum, and when he was at his peak, he overshot that to achieve genuine brilliance. It’s easy enough to tote up evidence of Malzberg’s prolificity: In his peak decade, from 1967 to 1976, Malzberg wrote at least 68 novels and seven story collections along with scores of still uncollected stories published in many magazines and anthologies. He worked in a variety of genres, including mystery, thrillers, erotica, and adventure fiction, but his core work was in science fiction.

Malzberg’s best science fiction novels—titles such as Beyond Apollo (1972), Herovit’s World (1973), Guernica Night (1975), and Galaxies (1975)—were astonishingly incisive critiques of modern technology and mass society. Intimately familiar with the genre, Malzberg used all the familiar SF tropes (space exploration, time travel, alternative histories) but amped them up with a bracing dose of pessimism and the stylistic bravura of literary modernism. Beyond Apollo tells the story of a doomed mission to Venus with an involuted, self-contradicting, sardonic, and half-mad narrator worthy of Samuel Beckett. Reviewing a Malzberg collection in 1980, the critic John Clute described “the sense of perplexity, of alarmed alienated implication, one feels on entering [Malzberg’s] calcined solipsistic universe.” This created, wrote Clute, “a world whose colors have been ashed down into a desolate, grey weirdly tonal inscape dominated” by a voice that was “grey, flat, intense, obsessive, unstoppable, almost always couched in the claustrophobic narrative-present tense, and seemingly humorless.” But that seeming lack of humor was, Clute went on to note, a misimpression. Once you caught the rhythm of his sly deadpan wit, Malzberg was also a hilarious writer.

Current Issue

Along with his peers J.G. Ballard, Samuel Delany and Philip K. Dick, Malzberg was a central figure in the movement of science fiction away from the external world of adventure fiction and outer space into the psychological torments and struggles of inner space. Technology, these writers all understood, is not something external to humans but changes how we think and how we feel: The registering of technological change in the realm of emotional life was their literary project.

Malzberg was a particularly kindred spirit to Dick, another speed demon—one who batted off books in a matter of weeks during amphetamine-fueled binge sessions at the typewriter. In an interview in the late 1970s, Dick said, “In all the history of science fiction, nobody has ever bum-tripped science fiction as much as Barry Malzberg.… he’s a great writer.”

Dick and Malzberg were ambidextrous in the same way: With one hand they wrote as pulp writers, and with the other as literary modernists. Pulps and modernism are usually treated as mutually hostile traditions: In contrast to the slapdash outpouring of words from the pulp writers, great modernists such as Flaubert and Virginia Woolf are notorious for agonizing over their words—the endless and painful quest to locate le mot juste.

Malzberg’s conflicting heritage of pulp fecundity and modernist ambition was rooted in his biography. Born in 1939—the son of a plywood salesman and a public school teacher—Malzberg aimed to be a writer from age 7. “I wanted to write because it was the only way I could deal with, control, and shape my experience,” he said in a 1979 interview. A classmate introduced Malzberg to science fiction magazines in 1951 and he soon became an avid reader. But it was a career as a literary writer in the mode of Norman Mailer or Philip Roth that he aimed for when he studied at Syracuse University in the late 1950s and early 1960s, where he won a Schubert Foundation fellowship for playwriting.

But the struggle to write plays and stories for small literary magazines proved unappealing to the working-class writer—especially after he married and had two daughters. He took on a variety of day jobs, working as a welfare officer and also as an evaluator for the Scott Meredith literary agency. In that period he discovered that writers of real literary ambition were able to make a living writing for genre outlets, notably science fiction magazines.

In a 1979 interview, Malzberg recalled that in 1965, “I was being rejected. I was writing literary short stories and drowning in rejections and I just did not want to go any further. In October or November of that year I read in Galaxy magazine Norman Kagan’s story ‘Laugh Along with Franz.’ It was a brilliant, savage piece of science fiction, except it wasn’t science fiction at all, it was a serious, savage work of American fiction by a young American fiction writer. I shook my head as I read it and I cynically said to myself, if this son of a bitch can get away with this kind of stuff in the commercial science-fiction genre then I’ve got a future.”

Malzberg’s efforts to marry modernist literary values to the pulp tradition made him a polarizing figure in the SF world. While he was extravagantly praised by fellow writers such as Philip K. Dick, Brian Aldiss, and Theodore Sturgeon, Malzberg also provoked a backlash from those who objected to the bleakness of his vision. A powerful strain of American science fiction, written under the aegis of the influential editor John W. Campbell of Analog magazine, was ideologically committed to technological optimism. The space program, in Campbellian science fiction, was proof that humanity could be triumphant and conquer the universe.

A life-long depressive, Malzberg had little use for can-do technological boosterism. In Malzberg’s gothic vision, technology was “the engines of the night”: the machines that can and probably will kill us. Ironically, in 1973 Malzberg’s Beyond Apollo won the first John W. Campbell Memorial Award for Best Science Fiction Novel, created after the editor’s death. This provoked howls of outrage among science fiction traditionalists, who henceforth made Malzberg’s name a shorthand for the corrupting of the genre.

In 1983, Carter Scholz wrote in The Comics Journal the single best appreciation of Malzberg. Scholz argued that the gothic vision of “the engines of the night” was aligned with the deepest currents of American fiction. According to Scholz:

These are the engines of the night. These are the ageless horrific dreams of Washington Irving, the morbid fantasies of Poe, the dark fauns of Hawthorne, the crazed thunder of Melville, the wicked grin of Twain, the blood rituals of Lawrence, the mad fallen saints of Faulkner, the uprooted myths of O’Connor or Welty, the enervated hysteria of Oates, the lush obsessions of Hawks, the fragmentary scatology of Burroughs—this is the literary tradition of American SF [science fiction], and Malzberg has seen that, but he has seen also that it is not just a matter of art, no longer, it is a matter now of our blood; for the first time, the engines are not just in the mind’s night, for the first time in history they are being built. Technology is the expression of the Gothic dreams of the technicians. And the machines, by this reckoning, cannot fail to kill us.

Malzberg knew the machines were changing us because he himself had been part of the process. To make a living as a pulp writer, he turned himself into a human machine—a kind of ChatGPT avant la lettre. This process of becoming a human text generator drove Malzberg, as himself admitted, half mad. It informs all his best work, giving them an authenticity of lived experience.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

By 1977, with the smash success of Star Wars, Malzberg’s somber and brooding fiction lost whatever cachet it once had. The dominant note of the genre returned to escapist adventure yarns. Malzberg, increasingly at odds with science fiction fans, wrote his last novel in 1983, although he continued to be a fecund writer of short stories.

Malzberg’s dark vision did not win him a large readership, although he gathered around himself a cluster of young writers (notably Batya Swift Yasgur and Robert Friedman) for whom he was a mentor and sometime collaborator. Although he was a curmudgeon, Malzberg was much loved by those who knew him.

Malzberg also lived long enough to see green shoots of his reviving literary reputation. Over the last few years, Stark House Press has been doing a diligent and commendable job of bringing his books back into print. Kent Worcester’s A Cultural History of the Punisher (2023) includes a fine appreciation of the “Lone Wolf” series of books Malzberg published in the 1970s under the name Mike Barry—a rare example of vigilante fiction with a stark left-liberal social conscience. There are signs here and there, especially among Youtube book channels, that his major works of the 1970s are being rediscovered. Barry Malzberg was an admirable writer, but not an easy one to emulate. I’ll shamefacedly admit that I spent far more time laboring over this obituary than he took in writing at least one novel.

With a hostile incoming administration, a massive infrastructure of courts and judges waiting to turn “freedom of speech” into a nostalgic memory, and legacy newsrooms rapidly abandoning their responsibility to produce accurate, fact-based reporting, independent media has its work cut out for itself.

At The Nation, we’re steeling ourselves for an uphill battle as we fight to uphold truth, transparency, and intellectual freedom—and we can’t do it alone.

This month, every gift The Nation receives through December 31 will be doubled, up to $75,000. If we hit the full match, we start 2025 with $150,000 in the bank to fund political commentary and analysis, deep-diving reporting, incisive media criticism, and the team that makes it all possible.

As other news organizations muffle their dissent or soften their approach, The Nation remains dedicated to speaking truth to power, engaging in patriotic dissent, and empowering our readers to fight for justice and equality. As an independent publication, we’re not beholden to stakeholders, corporate investors, or government influence. Our allegiance is to facts and transparency, to honoring our abolitionist roots, to the principles of justice and equality—and to you, our readers.

In the weeks and months ahead, the work of free and independent journalists will matter more than ever before. People will need access to accurate reporting, critical analysis, and deepened understanding of the issues they care about, from climate change and immigration to reproductive justice and political authoritarianism.

By standing with The Nation now, you’re investing not just in independent journalism grounded in truth, but also in the possibilities that truth will create.

The possibility of a galvanized public. Of a more just society. Of meaningful change, and a more radical, liberated tomorrow.

In solidarity and in action,

The Editors, The Nation

More from The Nation

This year’s best music, our critic thinks, defied conventions of genre and doctrine, showing how hybrid and fluid the art has become.

Books & the Arts

/

David Hajdu

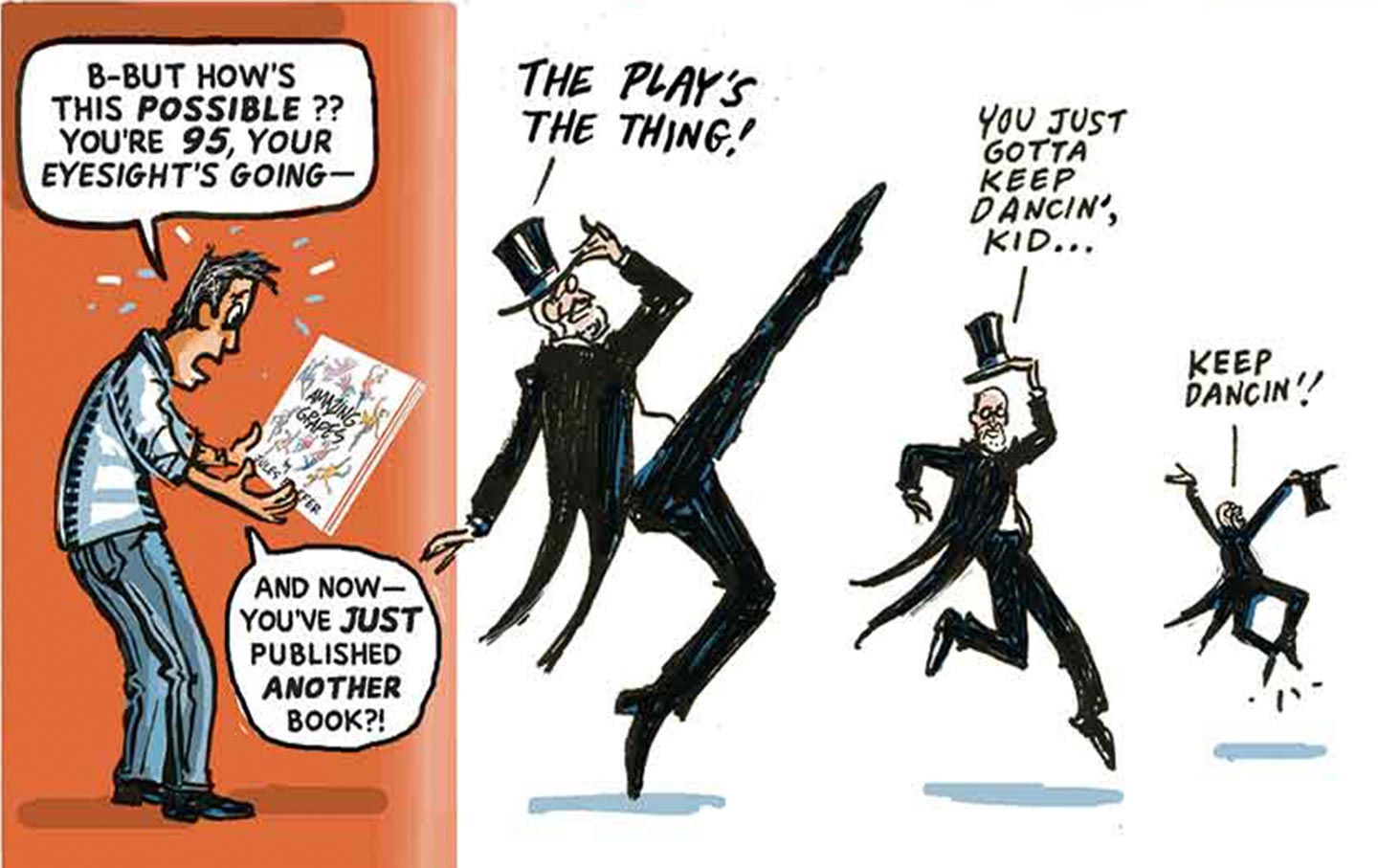

Cartoonist and writer Jules Feiffer is a national treasure. To mark his 95th birthday, we had some questions for the longtime Nation contributor.

Feature

/

Peter Kuper

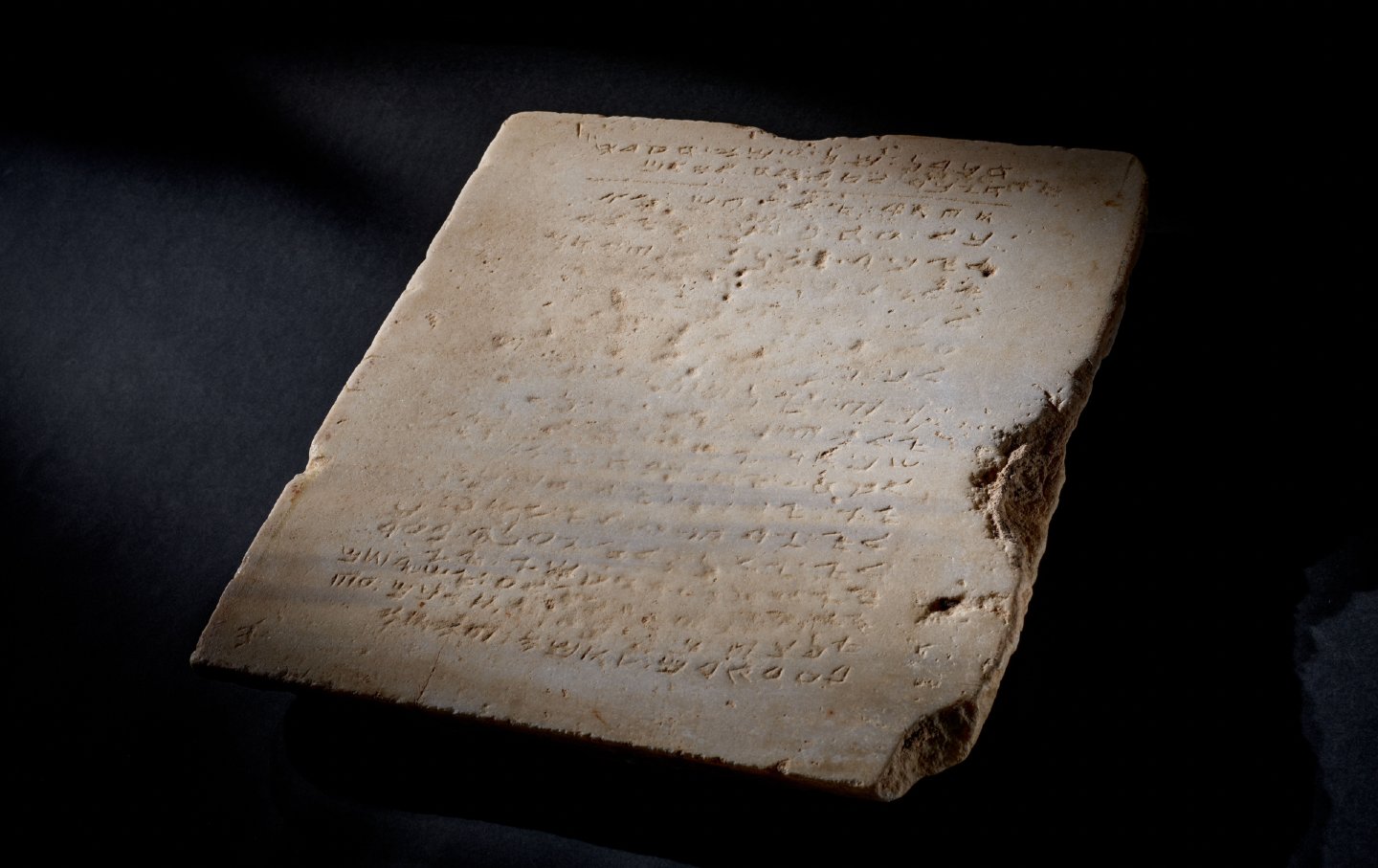

As the collections of Sir Moses Montefiore and David Solomon Sassoon go under the hammer today, what’s the future for rare books and historic artifacts in the age of generative AI…

David Brodsky

A film about survival, creativity, the hypocrisies of high art, The Brutalist tells a story about an architect who does not exploit and manipulate others to achieve his grand visi…

Books & the Arts

/

Kate Wagner

An avant-garde adaptation of Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer Prize–winning novel careens between questions of style and substance.

Books & the Arts

/

Stephen Kearse