Politics

/

January 13, 2025

When voters are consumed with anti-system rage, a criminal rap sheet is no barrier to high office.

Liberals have little enough to be cheerful about right now, so one can hardly begrudge a little glee at the news on Friday that a New York court declared Donald Trump a convicted felon over the hush-money payments he made to the adult film actress Stormy Daniels. There is certainly some satisfaction in Trump’s discomfort at the sentencing, as recorded by The New York Times: “Arms crossed, scowl set, President-elect Donald J. Trump avoided jail, but became a felon.” Trump’s conservative base was gratifyingly outraged. Fox News host John Roberts sputtered, “He is now branded, ah, Donald Trump with a scarlet letter of a big F on his forehead that he is a convicted felon.” Roberts went on to complain that the conviction was “ginned up…to taint Donald Trump.”

Conversely, tennis legend Martina Navratilova chortled, “Convicted felon Donald J. Trump does have a certain ring to it, no?” Other liberals elatedly listed the many countries where Donald Trump would be barred from entry as a felon (a joke that loses its bite once you realize that as American president he’ll easily be able to get a waiver to the normal rules).

Current Issue

If we step outside the immediate partisan reaction, Trump’s felony conviction seems like a small victory for liberalism that hides a larger catastrophic defeat. Even if we welcome the small symbolic justice of the felony conviction, there’s little to cheer about the fact that this conviction is for the least consequential of the criminal cases Trump has faced and that both the judge and prosecutor agreed there should be no punishment for it. As The New York Times reports:

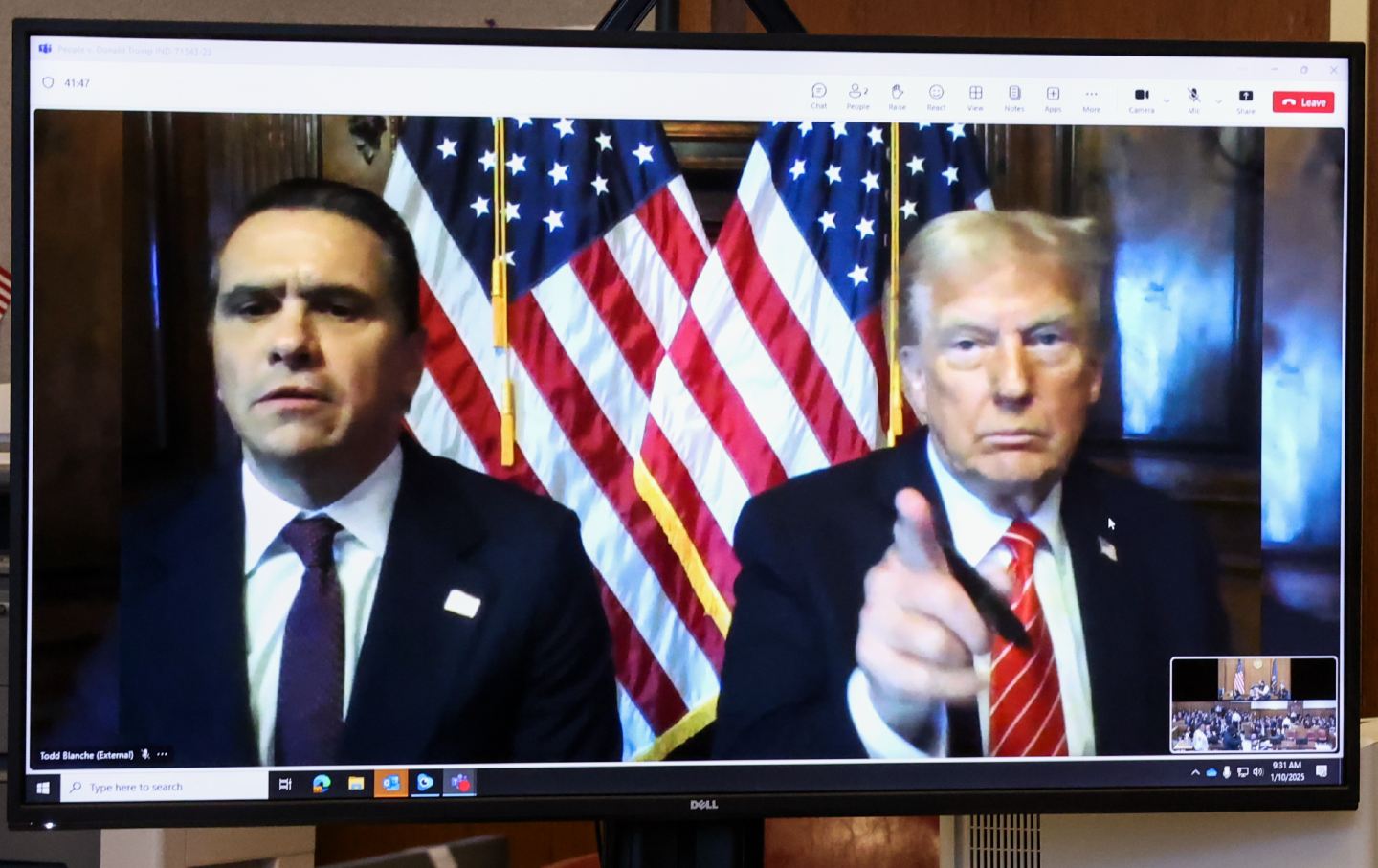

Trump once faced up to four years in prison for falsifying business records to cover up a sex scandal, but on Friday, he received only a so-called unconditional discharge. The sentence, a rare and lenient alternative to jail or probation, reflected the practical and constitutional impossibility of jailing a president-elect.

In other words, the conviction doesn’t reflect an end to Trump’s lifelong impunity but rather is another manifestation of that impunity. With Trump about to enter the White House, the other criminal cases against him are effectively over. On Friday, special counsel Jack Smith, who was overseeing the investigation of Trump’s efforts to overturn the 2020 election and his handling of classified documents, resigned. The Lincoln Project, a conservative anti-Trump group, caught the contradictions of the moment by noting, “Donald Trump ran for office to avoid punishment for his crimes, and it worked. The fact still remains that he is a 34 times convicted felon.”

In truth, Trump’s toothless felony conviction, coming on the cusp of his return to the White House, is no moment for jubilation: Rather, it should spur sober reflection among anti-Trump forces about the failure of prosecutorial liberalism. The use of prosecutors and courts to counter Trump has been the focus of much liberal energy over the last decade—but it is a failed strategy that has ended up only strengthening Trump.

Back in 2017, I wrote a column for The New Republic where I questioned the faith many liberals had that prosecutors such as Rod Rosenstein and Robert Mueller were on the verge of getting the goods on Trump and neutralizing him as a political force. I argued that

[relying] on Rosenstein and Mueller as barriers against Trump’s worst excesses is a prime example of a trap that liberals have fallen into time and again when dealing with presidential abuse of power—a tradition of “prosecutorial liberalism,” which seeks legal rather than political remedies to punish presidential misdeeds. Such an approach is dangerous because it allows legislators to pass off political problems to apolitical law enforcement officials.

In 2020, after the Mueller investigation had fizzled, I reflected in The Nation on the cultural and historical roots of prosecutorial liberalism.

The cult of Mueller was based on the dubious idea that a Republican and lifelong member of the Washington elite would pursue a relentless and scorched-earth investigation into a GOP president. This belief, in turn, rested on an idealization of federal law enforcement, seen as uncorrupted and rigorously loyal to the law. The liberals who joined the Mueller cult gave as much credence as any conservative to the cultural myths J. Edgar Hoover created in the early 20th century to legitimize the FBI. These myths paint federal lawmen as uniquely worthy: crew-cut upholders of justice who could be trusted more than politicians.

Even though prosecutorial liberalism has repeatedly failed, its hold on elite left-of-center opinion has only deepened. A big part of Kamala Harris’s political persona was the boast that she had been a tough-as-nails district attorney in California, so she’d be able to stand up to the arch-felon Trump.

In fact, not all voters loved Kamala-the-cop. Many on the left, animated by the police reform movement, saw her prosecutorial career as grounds to distrust her. A report on working-class people of color in the Bronx who had voted for both Donald Trump and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in 2024 documented that there was grassroots distrust of Harris’s prosecutorial record.

The problems with prosecutorial liberalism are twofold. First, it is a strategy that tries to use the legal system to do the work of politics. Of course, if figures like Trump commit crimes, they should fall under the purview of the law. But the law in and of itself is ill-equipped to settle the matter of a corrupt politician’s status with voters. There is a long history of voters rewarding politicians who run afoul of the law or have been entangled in scandal, beloved miscreants such as onetime Washington Mayor Marion Barry and onetime Louisiana Governor Edwin Edwards.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

The names Barry and Edwards highlight the second major problem with prosecutorial liberalism: It is a strategy that is counterproductive in an era of anti-system rage. Barry and Edwards were popular rascals precisely because their run-ins with the law reinforced their general populist stance. The fact that Barry was targeted as part of an FBI crack cocaine entrapment scheme only proved he was a threat to the system, which gave him credibility with working-class voters.

We live an age of anti-system rage, which has now expanded from impoverished areas like Washington, DC, and Louisiana to the entire United States. Trump’s popularity is due to the fact that he can give voice, however fraudulently, to anti-system anger. To counter Trump with FBI cardboard heroes like Robert Mueller or the liberal punitiveness of Kamala-the-cop serves only to legitimize Trump’s own claims that the powers that be oppose him.

Trump’s corruption and lawlessness remains a serious problem. But in his second term, liberals have to abandon the fantasy that there is a popular and legitimate legal system that can hold Trump accountable. Instead, the focus has to be on making a political case: Democrats need to show that Trump’s corruption is self-serving—that far from being a Robin Hood fighting for the common people, he is merely another plutocrat out for himself and his rich friends.

It’s possible, indeed likely, that Democrats will re-win control of the House of Representatives in 2026. If they do so, they will have a chance to engage in the political battles they have avoided until now: using the investigatory powers of Congress to genuinely investigate Trump’s abuse of power beyond the Russia-centered issues that are the main concern of the national security state. A further avenue of attack is the whole area of presidential power and elite impunity. The challenges of controlling the imperial presidency, which dominated politics in the era of Richard Nixon, urgently need to be revisited. Making a political case against Trump’s corruption won’t be easy—but it at least offers the hope of finding a systematic solution rather than just reverting to a prosecutorial liberalism that has repeatedly failed.