Politics

/

August 30, 2024

The GOP’s new league of fringe figures tries to replicate the party’s winning formula of 2016. And it just might work again.

When it comes to the politics of weirdness, pay attention to Donald Trump’s actions rather than his words. The Democrats have found an extremely successful gibe against Trump and his running mate, JD Vance, labeling them as weird. Trump and Vance have reacted to the “weird” accusation with a mixture of disdain and resentment. Speaking at a Pennsylvania rally on August 19, Trump took umbrage at the fact that the Democratic vice presidential nominee Tim Walz said “that JD and I are weird. I think we’re extremely normal people.” In his typical schoolyard manner, Trump added that their rivals Kamala Harris and Tim Walz were worse than weird. According to Trump, “Between [Walz’s] movement and [Harris’s] laugh, there’s a lot of craziness, I’d say a step further than ‘weird.’ ‘Weird’ is a nice word in comparison.” Speaking in Wisconsin on Thursday, Trump said of Walz, “He is weird, right? He’s weird. I’m not weird.”

Yet, even as Trump is trying to fend off or minimize the “weird” accusation, he continues to elevate the weird as part of a deliberate strategy. On Tuesday, Semafor reporter Dave Weigel claimed that Trump was going “all in” for the “weird vote” by elevating as campaign spokespeople figures such as Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Tulsi Gabbard—both former Democrats who have been relegated to the fringes for their heterodox views (Kennedy is an anti-vaxxer, and both he and Gabbard have been critical of some, although not all, forms of American foreign policy interventionism). While George W. Bush had to convene a somewhat dubious “coalition of the willing” to fight the Iraq War, Trump is assembling a coalition of the weird to defeat Harris and Walz.

The word “weird” is almost too gentle to describe Trump’s new team. Kennedy is known for his extremely eccentric personal history—which includes selling cocaine to fellow undergraduates at Harvard, keeping an extensive diary of his extramarital affairs during his first marriage, having a dead worm lodged in his brain, and bringing the carcass of a dead bear to Central Park in order to make it look like the animal was killed by a cyclist. Only last week, The New York Times reported that he once “Sawed the Head Off a Whale and Drove It Home,” according to his daughter Kick. With JD Vance turning off voters who see him as weird because of his reactionary gender politics, Kennedy is unlikely to help filter out the odor of weirdness around the Trump campaign.

When Gabbard endorsed Trump, Kennedy treated the announcement as if it were the expansion of a superhero team, tweeting, “Wonder Woman just joined the Justice League.” Along the same line, the official X account of the GOP tweeted out a photo that looked like a Justice League movie poster featuring Trump, Vance, Kennedy, Gabbard, and tech billionaire (and X owner) Elon Musk.

It’s telling that none of the figures shown with the former president supported him in 2016 or 2020, and all have spoken of him in vitriolic terms (according to The New Yorker, Kennedy earlier this year called Trump “a sociopath”). Kennedy is also, of course, the scion of a legendary political dynasty that has played a major role in Democratic politics for nearly a century.

As Weigel reports:

Democrats think they’re “weird.” The Trump campaign thinks they speak to persuadable voters—and enough of them to sway the election.

For months, Trump has stiff-armed party elders who were never comfortable with him, and elevated figures plugged into niche anti-establishment circles. From picking JD Vance, to courting Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. and addressing the Libertarian Party, Trump is betting that there’s an untapped well of support from voters—mostly white, mostly male—at the political margins.

They may not be large in number, but Republicans see them as up for grabs in an otherwise polarized electorate; people who might vote third party, or not at all, but can be brought into the GOP fold with the right care and attention.

Current Issue

This appeal to the weird includes a media strategy of appearing on niche podcasts that appeal to alienated voters (mainly young men) who cannot be reached by normal outlets. This strategy is a double-edged sword: In Jacobin and other publications, Vance has been accused of being too online and excessively amenable to advice from “Internet weirdos.” It’s true that on his frequent podcast appearances, Vance has often embarrassed himself, as when he agreed with a host that grandmothers helping with the raising of kids are fulfilling “the whole purpose of the postmenopausal female.”

But for the Trump campaign, such mishaps are worth the price of admission if they help get the message out to angry young men. As Weigel reports, “One Trump strategist said that the campaign now had six people who could credibly talk to anti-establishment podcasters with more viewers than nightly network news: Trump himself, his eldest sons, Vance, Kennedy, and Gabbard.”

The journalist Max Read describes this media strategy as “dipshit outreach.” Read paints a vivid picture of the types of podcasters and YouTube influencers Trump and his surrogates are using to get their message across:

This week, Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump made an appearance on the podcast of Road Rules and The Challenge contestant Theo Von, who has lately found success as a Zynternet-adjacent stand-up comic and podcaster. A clip from the podcast, in which Von describes the effects of cocaine to Trump, has gone somewhat viral, largely because it’s one of very few recent clips of Trump where he’s neither rambling nor bored. This interview comes on the heels of one with streamer Adin Ross earlier in August, and an interview with YouTuber/podcaster Logan Paul back in June; the same month, the Canadian pranksters of the YouTube channel “Nelk” recorded a TikTok on behalf of Trump’s vice-presidential candidate, Ohio senator J.D. Vance.

What do Von, Ross, Paul, and the Nelk Boys have in common? I’ll admit that it’s unfair to lump a harmless and affable dumbass like Von in with a malevolent little twerp like Ross. But they all provide varying levels of access to a large audience of young men who might find Trump appealing—guys who like “edgy,” trollish, hedonistic, attention-seeking personalities.

Read is skeptical that this “dipshit outreach” will pay off, since many of the listeners to these programs are not just low-propensity voters—they are actually too young to vote.

But Read might be too complacent. As strange as it may sound, the “coalition of the weird” strategy cannot be dismissed out of hand or seen as something that will automatically help Democrats. After all, a similar strategy helped Trump win in 2016.

As John Ganz noted in a 2023 Substack post, Trump’s victory in 2016 was based on his willingness to make a pitch to “any weird constituency.” The theory of the “coalition of the weird” goes like this: In a polarized America, both Democrats and Republicans have a base of around 47 percent of the vote that gives them a shot at winning. Elections are decided in swing states where victory depends on mobilizing especially passionate voters. If you can add to the base you already have a sufficient number of fringe voters with special issues, you can win. Thus in 2016, Trump made overtures to groups like Gamergaters (video game players who objected to feminist critiques of their hobby), goldbugs, the openly racist alt-right, and anti-vaxxers. These groups are all small in numbers, but they appreciated Trump’s willingness to echo their ideas and slogans. And together they gave him enough electoral juice to defeat Hillary Clinton. Since then, Trump’s coalition has expanded to included QAnon conspiracy theorists.

Trump’s current “coalition of the weird” is a reprise of this strategy. It’s a risky strategy because it helps power the Democratic argument that Trump and Vance are too weird to be allowed anywhere near the White House. But the Democrats also run the risk of alienating voters who are drawn to the more plausible and defensible positions advocated by figures such as Kennedy and Gabbard.

In a Substack post, journalist Ken Klippenstein described how he’s heard people who oppose Trump praise Kennedy’s speech endorsing Trump. This is Klippenstein’s account of the speech:

I watched the speech and got a taste of why his message resonates so strongly, despite the avalanche of news focusing on RFK’s bizarre personal history and his anti-vax stance. I came away not with an appreciation for RFK, but for the hunger people clearly feel for someone, anyone to talk about the issues he raises. He resonates not because of any clarity of thought or grasp of the issues or the solutions he advances. The appeal is in the problems he identifies—from endless wars like in Ukraine to the utter failure of the U.S. healthcare system—which Trump and Kamala Harris have been disinclined to discuss.

Klippenstein is right that there has been a dearth of serious and plausible policy statements from either candidate on the large problems facing America. One could expand his list to include the escalating war in the Middle East, which is an even more striking case because on that issue Kennedy and Gabbard are just as hawkish as mainstream Democrats and Republicans.

In the absence of real politics, some part of the public will be attracted to fringe characters who at least promise a change. By creating a “coalition of the weird,” Trump is conjuring an illusion for those voters to suggest that he could be a change candidate.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Currently, Kamala Harris is leading in the polls, and there are certainly reasons to be optimistic about her chances. But if the race tightens, Democrats will have to confront the fact that the “weird” label only gets you so far. In the absence of genuine hope, and meaningful change, weird could win again.

Or as Hunter S. Thompson long ago taught us, “when the going gets weird, the weird turn pro.”

Can we count on you?

In the coming election, the fate of our democracy and fundamental civil rights are on the ballot. The conservative architects of Project 2025 are scheming to institutionalize Donald Trump’s authoritarian vision across all levels of government if he should win.

We’ve already seen events that fill us with both dread and cautious optimism—throughout it all, The Nation has been a bulwark against misinformation and an advocate for bold, principled perspectives. Our dedicated writers have sat down with Kamala Harris and Bernie Sanders for interviews, unpacked the shallow right-wing populist appeals of J.D. Vance, and debated the pathway for a Democratic victory in November.

Stories like these and the one you just read are vital at this critical juncture in our country’s history. Now more than ever, we need clear-eyed and deeply reported independent journalism to make sense of the headlines and sort fact from fiction. Donate today and join our 160-year legacy of speaking truth to power and uplifting the voices of grassroots advocates.

Throughout 2024 and what is likely the defining election of our lifetimes, we need your support to continue publishing the insightful journalism you rely on.

Thank you,

The Editors of The Nation

More from The Nation

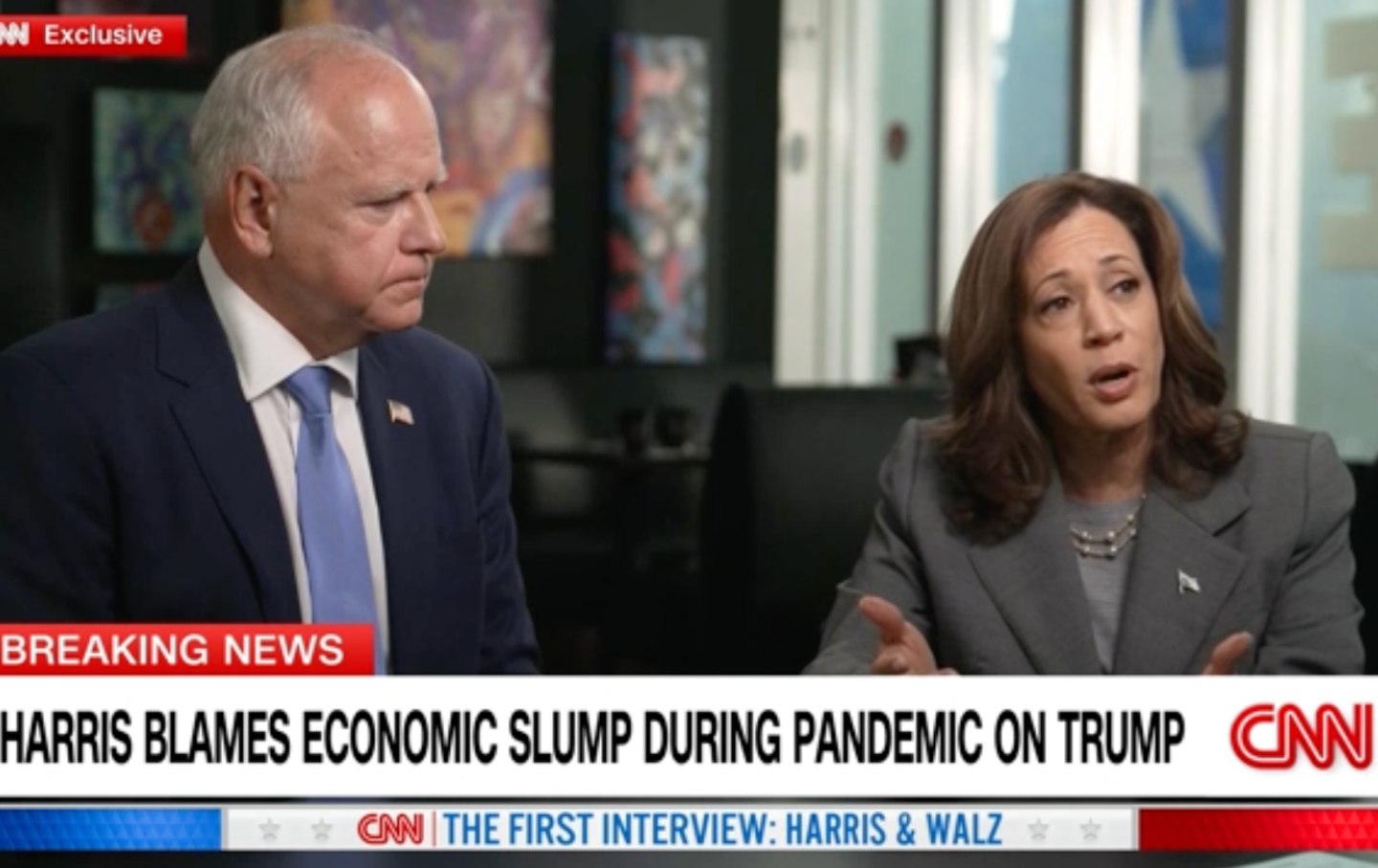

Harris and Walz held their own during an interview driven more by media-made controversies than substance.

Joan Walsh

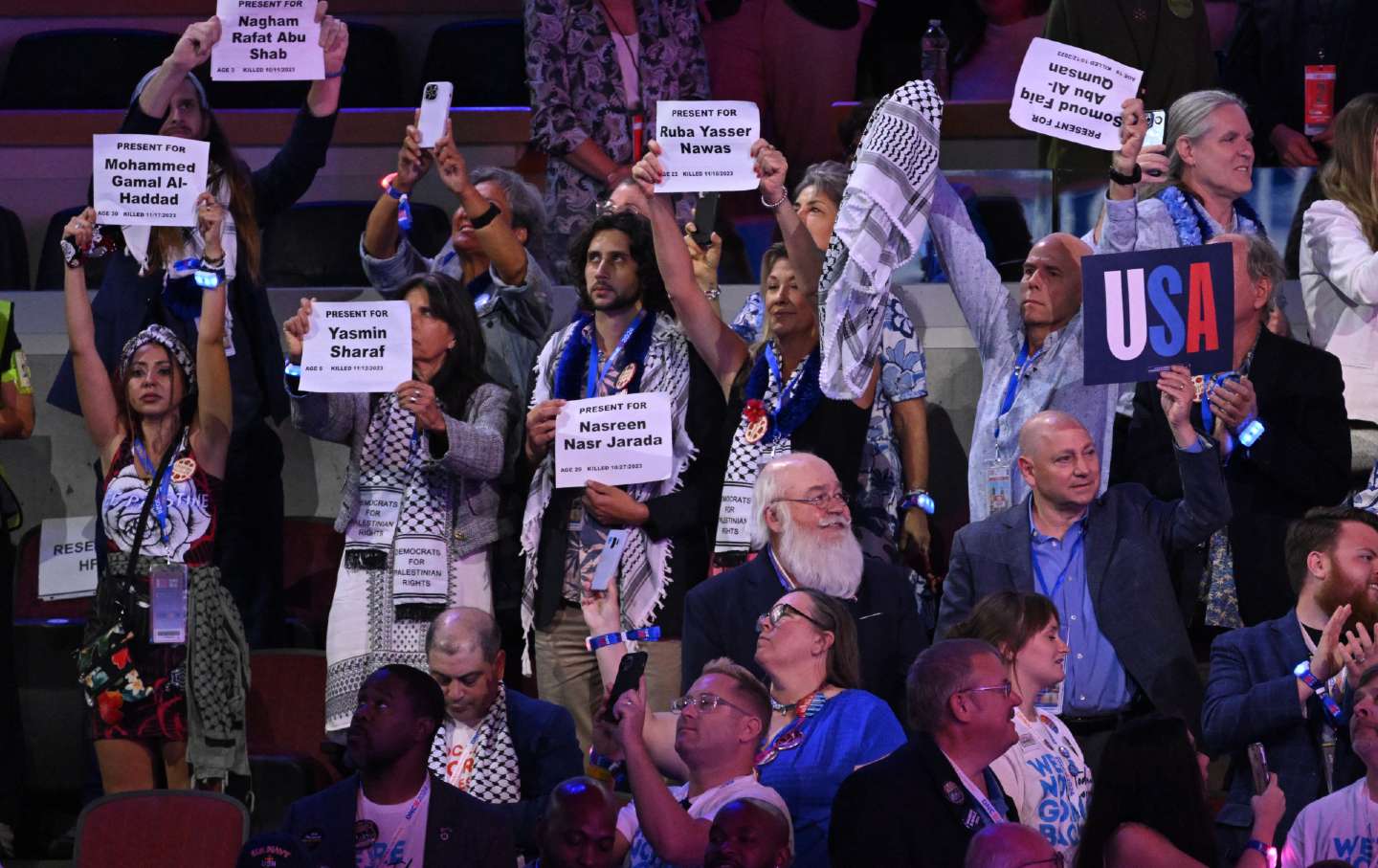

But the hope I felt when she became the nominee has been curdling into despair over her refusal to allow a Palestinian to address the convention—and her continuing silence on Gaza…

Benjamin Moser

Should Kamala Harris win in November, her attorney general pick will be among her most critical cabinet appointments. Progressives should start organizing now.

Elie Mystal

Pamela Price, the Alameda County DA, is fighting a recall vote and to defend her unwavering refusal to over-criminalize young people.

Piper French

A lack of knowledge about the process—from registration to marking a ballot—is often the main barrier between youth and voting. “If young people sit it out, that will have an impa…

StudentNation

/

Aminata Gueye and Nikole Rajgor